There has been rain and that means it’s weeds and spraying time. This time of year also lends itself to extremely risky spray conditions. Beautiful autumn weather is when surface temperature inversions are most common. For more information on inversions read my previous blogs here and here.

Strong inversion conditions March 2016. Image: AGRONOMORemember that all pesticides drift, it is just that some, such as Group I herbicides like 2,4-D, have a recognisable odour and produce unique symptoms on sensitive vegetation.

Strong inversion conditions March 2016. Image: AGRONOMORemember that all pesticides drift, it is just that some, such as Group I herbicides like 2,4-D, have a recognisable odour and produce unique symptoms on sensitive vegetation.

So what is the problem with off-target movement of pesticide? The most obvious agricultural issue is damage to sensitive crops. For example in the 2007-08 cotton growing season it was estimated that 10 per cent of the Australian cotton crop has some level of herbicide damage costing $5 million.

The second agricultural issue is pesticide residues. Organic farmers certainly don’t want anyone else’s pesticides. Drift is a particular problem when a crop is getting close to harvest. Signing a vendor declaration that you haven’t used certain pesticides gets complicated when the purchaser tests the product and it is ‘contaminated’.

Some of our major trading partners also have zero tolerance for certain pesticides. Ship loads of grain have been turned around and sent back for such breeches. The wine grape industry is particularly aware of the potential effects of unwanted residues on their markets.

Contamination of the natural and human environments is also a major concern.

Sensitive areas

Other than showing a duty of care, reading and following the label, using buffer zones and using best practice application, we need to be aware of sensitive areas in the vicinity of the farm when spraying. Talk to your neighbours and find out what crops they will have in, particularly in paddocks along the boundary. Be aware of state restrictions on pesticide use and spraying.

Some Australian states have restrictions on spraying in or near ‘sensitive’ areas. Western Australia has listed most Group I herbicides as ‘Scheduled’ meaning they cannot be used within certain distances of sensitive crops and high volatile 2,4-D ester is banned within 5 km of a commercially sensitive crop (vineyards or tomatoes), within 19 km of the Geraldton post office and within the Swan Valley, or within 10 km of the Kununurra Post Office. High volatile ester is not registered any other state or territory.

Victoria has nine designated areas where the type of pesticide and its application is regulated.

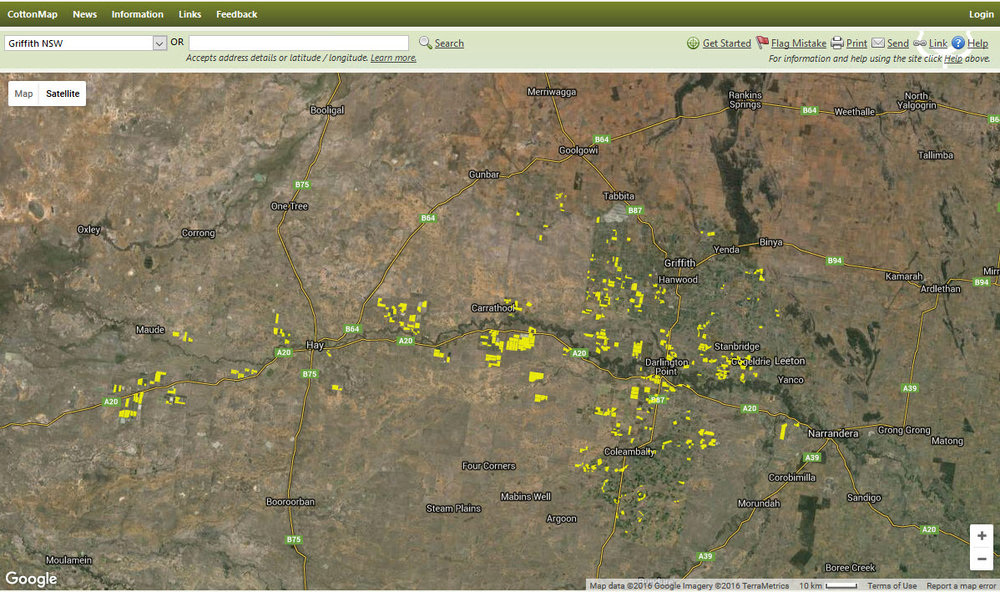

Agricultural Chemical Control areas in Victoria. Source: Agriculture VictoriaThe cotton industry has led the way with on online mapping with 95% of cotton crops mapped. There is no excuse to say you didn’t know there is cotton nearby.

Agricultural Chemical Control areas in Victoria. Source: Agriculture VictoriaThe cotton industry has led the way with on online mapping with 95% of cotton crops mapped. There is no excuse to say you didn’t know there is cotton nearby.

Cotton field awareness map for the western Riverina. Source: Cotton Australia & Cotton CRDCWestern Australia also has a voluntary system of registering your pesticide sensitive crop with the Department of Agriculture & Food WA.

Cotton field awareness map for the western Riverina. Source: Cotton Australia & Cotton CRDCWestern Australia also has a voluntary system of registering your pesticide sensitive crop with the Department of Agriculture & Food WA.

DAFWA sensitive areas map 2015The map highlights organic farms, vineyards, tree crops, vegetable, bee hives and aquaculture sites. Being voluntary not all WA sensitive crops are mapped and a quick comparison with Google Earth will show additional vineyards and orchards. Another problem is that most broadacre farmers I have spoken with are unaware that this map of sensitive crops exits. This is ironic because much of the potential drift affecting these sensitive crops could come from cropping country.

DAFWA sensitive areas map 2015The map highlights organic farms, vineyards, tree crops, vegetable, bee hives and aquaculture sites. Being voluntary not all WA sensitive crops are mapped and a quick comparison with Google Earth will show additional vineyards and orchards. Another problem is that most broadacre farmers I have spoken with are unaware that this map of sensitive crops exits. This is ironic because much of the potential drift affecting these sensitive crops could come from cropping country.

When it is spray time, do some planning, look at the weather forecast and for any potential risks, talk to your neighbours, use the right gear and get that pesticide where it is meant to be.