It is that time of year again when a farmer’s thoughts turn to burning. Like most things there is more than one way to skin a cat. However I am going to talk about some of the dos and don’ts for narrow windrow burning.

Although at this point you cannot do anything about chaff windrows that have already been produced what you will see is that windrows from a well set up header will have withstood considerable amounts of rain over summer and still be ready to burn. The windrow you can see below has had over 100 mm of rain between harvest and burning.

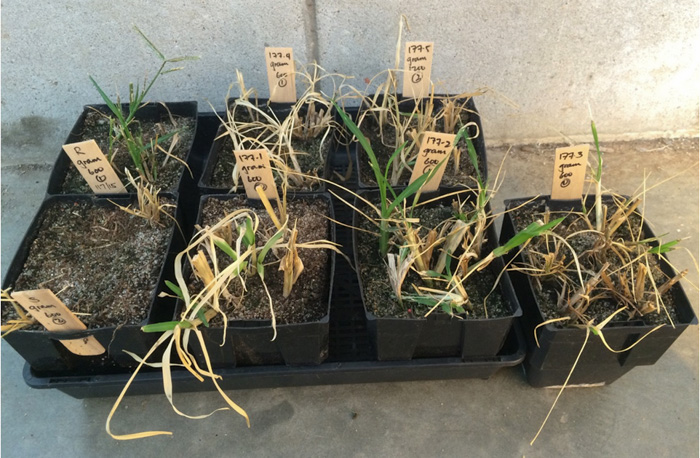

Windrows that aren't over-threshed remain open and aerated like this one.

Chaff still on top of windrow despite 100 mm rain.Things to note are that the windrow appears prickly and this shows that during harvest the straw was not over threshed. This has allowed the chaff portion to remain high in the windrow which also aids drying after rain. The crop was harvested at a height of approximately 10 cm.

Another critical factor in burning windrows is the meteorological conditions when you start burning.

Starting the burn when the FDI is about 7 which in this case was about 18:00.The use of a fire danger index (FDI) has made stubble burning more of a science than a mystical art. The FDI is determined by temperature, humidity, wind speed and dryness of the fuel. These need to be measured and put into the fire index app to calculate FDI. This means that you need a weather meter, either hand-held or cab mounted, and your mobile phone with the app installed. A very useful app for both Android and Apple is Fire Tools by Mountain Pine Studios.

Doug Smith measuring wind speed, temperature and humidity to feed into the fire app. Also use the Bureau of Meteorology’s MetEye® site for monitoring local predicted changes to wind speed and direction so you can decide whether to press on or call it a night.

This is the sort of result you aim for.As a rule of thumb for the fire index:

Greater than 15 is too high

8 to 10 is ideal

Less than five is often too cool or damp

Starting when the fire index is too high means that the file will rarely stay in the windrow and the fire will burn significant portions of the paddock. See image below.

Too low and the windrows won’t burn as hot as needed to kill weed seeds in the row.

This paddock on another property was cut a little high and the burn started when the Fire index as too high. The fire didn't remain within the rows.Important pointers from Doug & Kerry Smith, Pingrup, WA

- Always over-estimate the problem and under-estimate your ability when it comes to fire control

- Your aim is to burn the rows not the farm

- Buy a good fire lighter as it makes a big difference to the amount you can light per night

- Conditions change by the hour so keep measuring conditions as well as knowing what is coming for the next couple of days before you light up.

- Check for smouldering rows early the next day so they can be dealt with before the day heats up.