Another three weed species in Australia have just confirmed resistant to paraquat – Cudweed (Gamochaeta pensylvanica), blackberry nightshade (Solanum nigrum) and crowsfoot grass (Eleusine indica) taking the total number of species to 9 in Australia (Table 1).

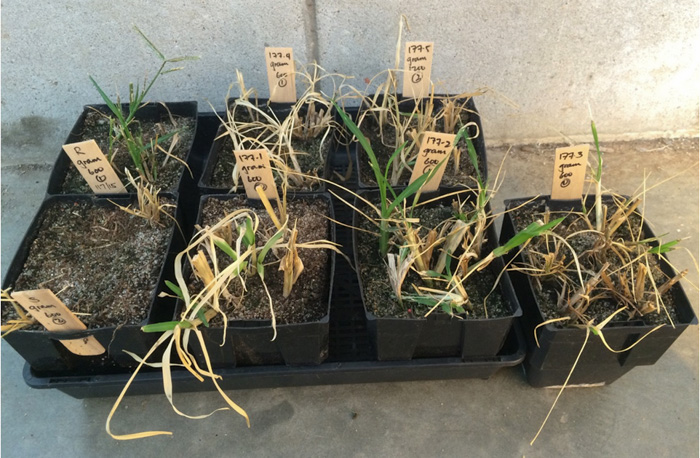

Paraquat resistant crowsfoot grass regrowing following spraying. Image: P. Boutsalis & C. Preston

Paraquat resistant crowsfoot grass regrowing following spraying. Image: P. Boutsalis & C. Preston

Overseas there are now 24 species resistant to paraquat, from the Middle East through to New Zealand, comprising of 6 grass and 18 broadleaf species.

Table 1 Species that have developed paraquat resistance in Australia

(Australian Glyphosate Sustainability Working Group)

|

Species |

Common name |

Year first confirmed |

State |

Crop |

Resistance to other herbicides / MOAs |

|

Arctotheca calendula |

Capeweed |

1984 |

Victoria |

lucerne |

Diquat (L) |

|

Hordeum glaucum |

Northern barley grass |

1983 |

Victoria |

lucerne |

Diquat (L) |

|

Hordeum leporinum |

Barley grass |

1988 |

Victoria |

lucerne |

Diquat (L) |

|

Vulpia bromoides |

Silver grass |

1990 |

Victoria |

lucerne |

Diquat (L) |

|

Mitracarpus hirtus |

Small square weed |

2007 |

Queensland |

mangoes |

Diquat (L) |

|

Lolium rigidum |

Annual ryegrass |

2010 |

South Australia |

Pasture seed |

A / M - 2 populations |

|

Gamochaeta pensylvanica |

Cudweed |

2015 |

Queensland |

Tomatoes, peanuts, sugar cane, avocados |

|

|

Solanum nigrum |

Blackberry nightshade |

2015 |

Queensland |

Tomatoes, peanuts, sugar cane, avocados |

|

|

Eleusine indica |

Crowsfoot grass |

2015 |

Queensland |

Tomatoes, peanuts, sugar cane, avocados |

|

As can be seen from Table 1, paraquat resistance hasn’t developed in broadacre cropping yet and the listed rotations, or lack of them, were highly reliant on paraquat for weed control. However the widespread adoption of paraquat either as a second knock or an alternative to glyphosate over the past 10 years we probably don’t have long to wait. There are rumours of a glyphosate-paraquat resistant population of annual ryegrass (L. rigidum) about to confirmed from southern Western Australia.

In 2013 we confirmed a ryegrass population from a Great Southern vineyard that is strongly resistant to both glyphosate and paraquat which was the result of a vineyard manager rotating between these two important herbicides. Rotating herbicide modes of action buys you time, but doesn’t prevent resistance.

The answer?

The only way to stop herbicide resistance in its tracks is ensure no survivors of a herbicide application are allowed to set fertile seed.

This means drive weed numbers down and use diverse crop rotations, which in turn gives you plenty of options to use a range of non herbicide weed tactics. Combined with competitive crops, good timing of operations and effective spray practices you are on the way to putting herbicide resistance well into the future.

While tank mixing solid rates of different modes of action can be effective, many growers will be too late for this tactic as they already have resistance to at least one of these modes of action. For tank-mixing to work as a resistance management strategy both herbicides MUST BE fully effective on the weeds in question.

Mixing glyphosate and paraquat is not a viable option because of antagonism (biological) in the plant. When mixed together these products are not complementary and the paraquat works too rapidly for the glyphosate to be effectively translocated. This is the reason the double knock is utilised. Both products can be utilised on the same weed population without antagonism of the mix.

But before you go, ask yourself the question, “How do I know which of my herbicides still work?”

Blackberry nightshade Image: AGRONOMO

Blackberry nightshade Image: AGRONOMO

An update on the paraquat resistance story - it has now been confirmed by the University of Adelaide and the Australian Glyphosate Sustainability Working Group that a population of flaxleaf fleabane (Conyza bonariensis) has been found to be resistant to 4 L/ha of paraquat.

The population developed in wine grapes in the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area in New South Wales.

Paraquat resistant fleabane (L) and susceptible fleabane (R). Image: P. BoutsalisThis poses significant issues for weed management in vines and tree crops as more paraquat is being used to manage glyphosate resistant weeds.

Paraquat resistant fleabane (L) and susceptible fleabane (R). Image: P. BoutsalisThis poses significant issues for weed management in vines and tree crops as more paraquat is being used to manage glyphosate resistant weeds.

Over-reliance on glufosinate will ultimately lead to glufosinate resistance.

A diverse range of weed management tactics needs to be considered which will most likely include the use of pre-emergent herbicides.

For more information on paraquat and glyphosate resistance go to the Australian Glyphosate Sustainability Working Group web site - http://www.glyphosateresistance.org.au/index.html